What does “secondary air pollution” actually mean indoors?

28 January 2026

Key points

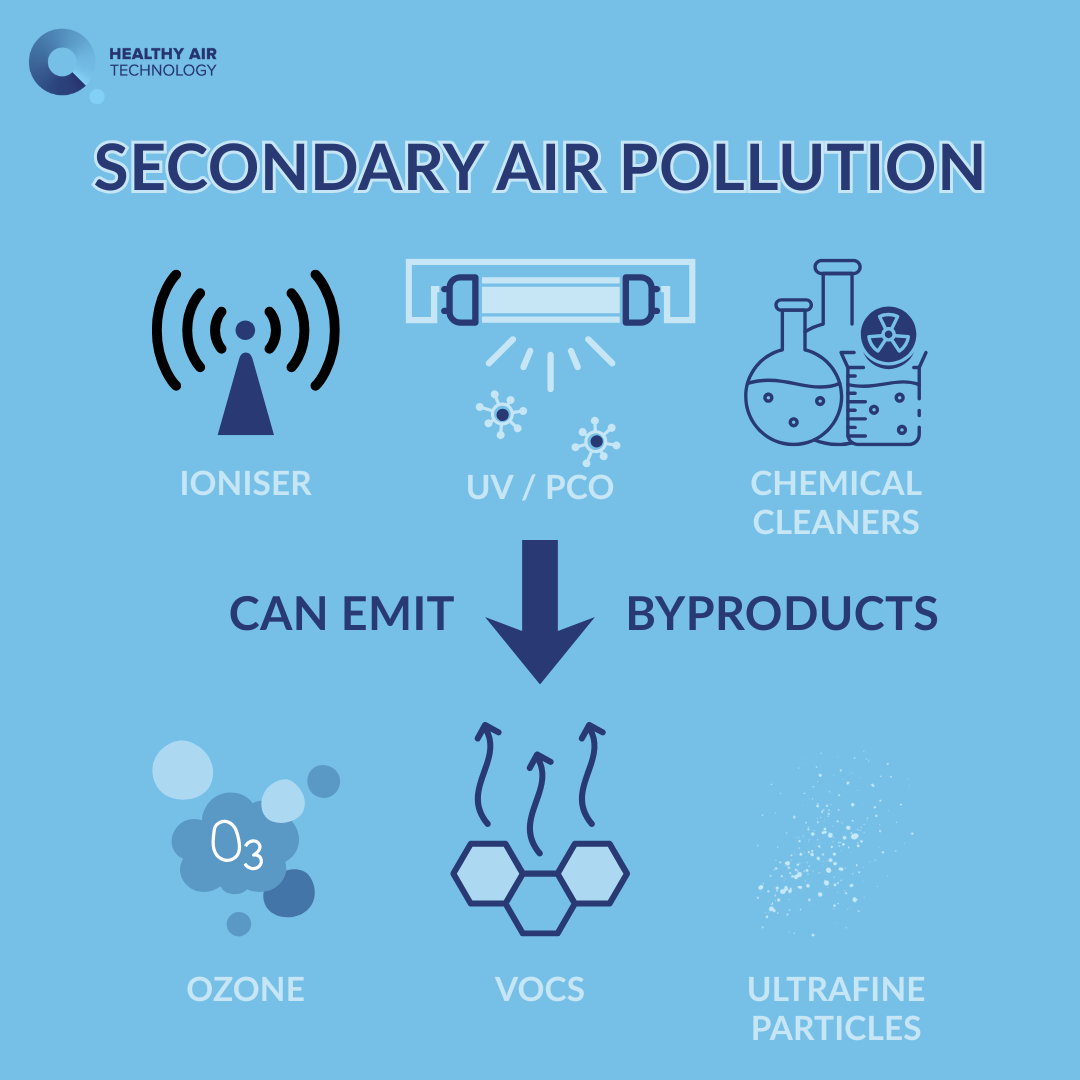

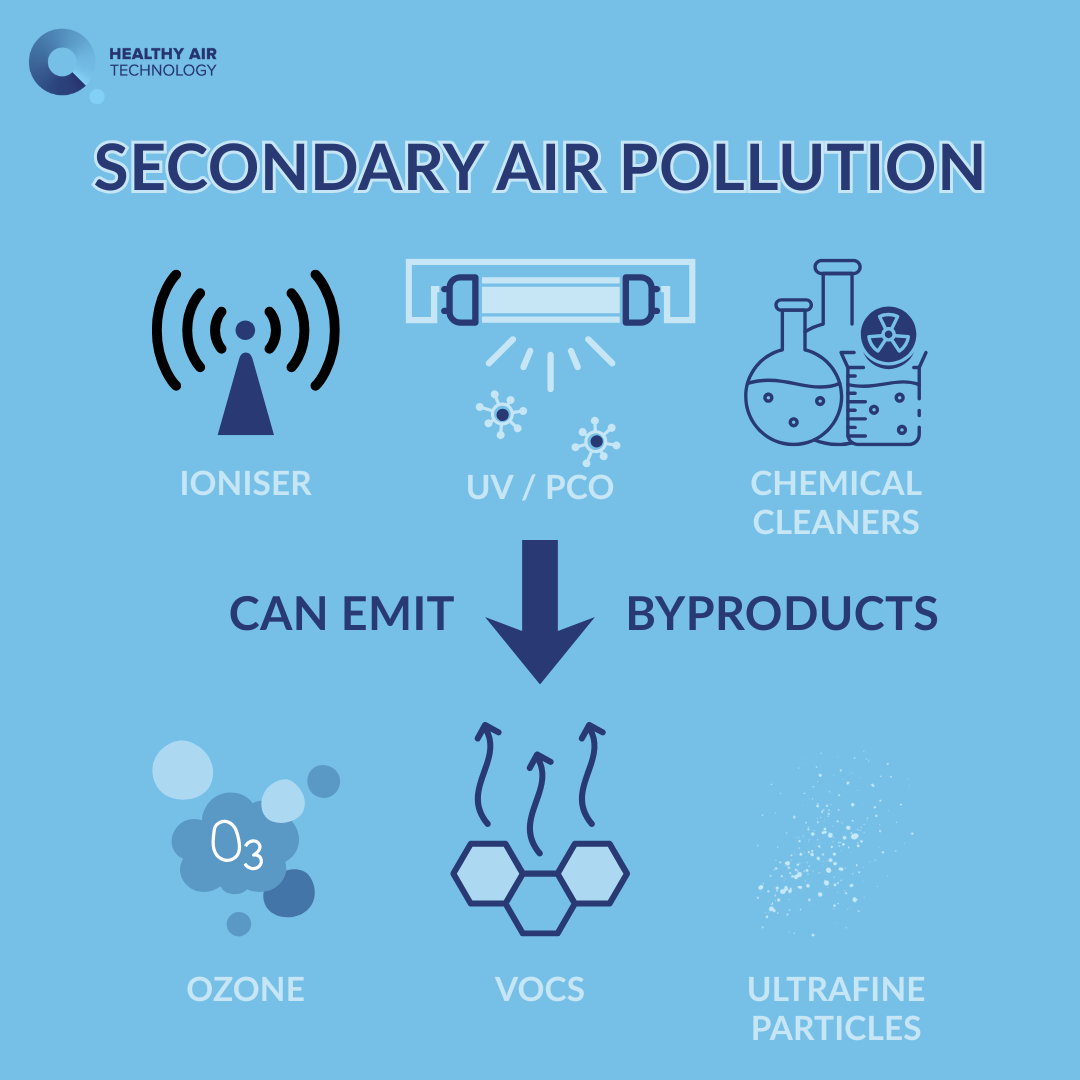

- Secondary air pollution refers to new pollutants or re-released contaminants created as a side effect of air cleaning, disinfection or filtration processes.

- It usually appears in two forms: chemical by-products (e.g. ozone, NOₓ, oxidised VOC fragments) and secondary release from filters or surfaces.

- Certain technologies (e.g. ozone-generating devices, some plasma or UV/PCO systems, frequent chemical fogging) can contribute to secondary chemical pollution if not well controlled.

- Conventional filters can contribute to secondary release if captured particles or microbes are not inactivated and are later dislodged or disturbed.

- Catalytic systems such as D-orbital nano oxide (DNO) are designed to keep reactive chemistry confined to solid surfaces and to mineralise pollutants, helping to reduce the risk of secondary pollution in the occupied space.

When people install an air purifier or disinfection system, they usually expect it to reduce pollution and risk. In practice, some approaches can also create new pollutants or re-emit previously captured material.

This phenomenon is called secondary air pollution. Understanding it is important when comparing technologies and when interpreting test results and monitoring data in real buildings.

How is secondary air pollution different from primary pollution?

What is primary pollution?

Primary pollutants are the contaminants that are already present in the air. Typical examples include:

- Fine particles such as PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀

- Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from materials, products and activities

- Combustion-related gases such as nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) and sulphur dioxide (SO₂)

- Bioaerosols such as bacteria, viruses, mould spores and pollen

These come from sources like traffic, gas cooking, cleaning agents, office equipment, occupants and damp building elements.

What is secondary air pollution?

Secondary air pollution refers to:

Pollutants that are formed or re-mobilised as an unintended consequence of an indoor air cleaning or disinfection method.

Indoors, this usually falls into two categories:

- Chemical by-products – new gases or reactive species produced by high-energy or chemical processes.

- Secondary release – previously captured particles or microorganisms that are reintroduced into the air from filters, ducts or surfaces.

The important distinction is that primary pollutants are what you start with; secondary pollutants are what you might inadvertently add during the attempt to remove them.

How do air cleaning processes create chemical by-products?

Several technologies use strong oxidising conditions to break down pollutants and inactivate microbes. If the chemistry is not fully confined, it can generate secondary chemical pollutants in the occupied space.

Ozone generators and some ioniser/plasma systems

Certain devices produce ozone (O₃) and radicals to oxidise pollutants. This can leave residual ozone and also form new compounds, including oxidised VOCs and fine secondary particles. Where ionisers or plasma devices are used, it is important to know whether they generate any measurable ozone or other by-products at the operating settings used with occupants present.

UV and photocatalytic oxidation (PCO) systems

UV and PCO technologies use UV light and a catalyst (e.g. titanium dioxide) to generate reactive oxygen species at the surface that can oxidise VOCs and inactive microbes.

However, if the reactions are not fully confined to the catalyst surface, radicals or intermediate compounds may escape and generate trace ozone or partially oxidised VOCs in the bulk air.

Chemical sprays and fogging agents

Disinfectant sprays (e.g. bleach, hydrogen peroxide, quaternary ammonium compounds, etc.) are widely used for surface cleaning. But when used as sprays can leave residual chemicals or reaction products in the air, especially if used frequently or in poorly ventilated spaces.

These products should be regarded as one element in an infection-control strategy, with attention to ventilation and exposure, rather than as a long-term method for “treating” room air.

What is “secondary release” from filters and surfaces?

Even when no new chemicals are formed, an air treatment system can still contribute to secondary pollution through secondary release.

How does secondary release occur?

Mechanical filters (including high-efficiency types such as HEPA) are designed to capture particles and bioaerosols. Over time:

- Dust, allergens and microorganisms accumulate in the filter media.

- If they are not chemically inactivated, they remain present in that structure.

- Airflow changes, vibration, handling or moisture can dislodge some of this material.

As a result, some fraction of previously captured particles or microbes can be released back into the airstream. This is:

- Most likely when filters are old, overloaded or disturbed (e.g. during replacement).

- Still possible at a low level during normal operation if no additional inactivation mechanism is present.

Why is this important?

From a building-management perspective:

- A purely passive filter behaves as a reservoir of contaminants once they have been captured.

- Without inactivation, it relies entirely on physical retention and careful handling to prevent release.

- The concept of “secondary release” emphasises that filtration alone does not eliminate the contaminant; it relocates it.

This is one reason why some systems combine filtration with UV or catalytic treatments aimed at deactivating what the filter has captured.

Technologies and Their Relationship to Secondary Pollution

The table below summarises the main mechanisms frequently discussed in indoor air quality and how they relate to secondary pollution.

| Technology type | Primary action | Secondary pollution risk |

| Ozone generators / some plasma systems | Oxidise pollutants in bulk air | Ozone, NOₓ, reaction by-products in the room |

| UV/PCO systems | Surface/catalyst oxidation | Possible oxidants or fragments if not well-controlled |

| Chemical sprays/fogging | Surface disinfection | Residual chemicals, reaction products in air |

| Mechanical (HEPA) filters | Physical capture of particles | Secondary release of trapped material if not treated |

| Catalytic filters (e.g. DNO-based) | Capture plus surface-bound oxidation | Designed to minimise by-products in the bulk air |

The key distinction is between technologies that create reactive chemistry in the room air versus those that confine reactions to a solid surface.

How do catalytic systems like DNO aim to avoid secondary pollution?

One approach to reducing secondary pollution is to keep all high-energy chemistry confined to solid surfaces rather than the air, and to mineralise pollutants.

What happens at a DNO catalyst surface?

Healthy Air Technology’s devices are built around D-orbital nano oxide (DNO) catalysts, developed with academic researchers at Oxford University. They are based on:

- Transition metal oxides (for example, manganese, zinc and silver oxides)

- Supported on high-surface-area material, often hydrophilic (e.g. zeolites or alumina), so that pollutants and bioaerosols are efficiently trapped at the surface

- Integrated with mechanical filtration (e.g. HEPA) to give both physical capture and chemical destruction

In simplified terms:

- Pollutants (gases, VOCs, bioaerosols) are adsorbed onto the catalyst surface, often aided by the hydrophilic support.

- Oxygen from the air is activated at the metal oxide sites, forming surface-bound active oxygen species.

- These species react with the adsorbed pollutants, breaking them down into more stable end products (typically carbon dioxide, water and benign solid species).

- The active oxygen remains bound to the surface; it is not released as ozone or free radicals into the room.

This combination of adsorption and surface-confined oxidation is designed to remove pollutants from the air while avoiding generating ozone or other strong oxidants in the occupied space and reducing the risk of secondary chemical pollution.

How does this relate to secondary release?

In devices that integrate high-efficiency particle filtration (e.g. HEPA) and DNO catalytic layers, the intent is that:

- Particles, including bioaerosols, are captured by the filter.

- At the same time, the catalyst promotes the inactivation and breakdown of organic material and certain gases at or near the filter surface.

In principle, this reduces the likelihood that viable microorganisms or reactive gases will later be re-emitted, because the contaminants are being deactivated rather than simply stored.

What Does Secondary Pollution Look Like in Practice?

From a measurement point of view, secondary pollution can appear in several ways.

Chemical indicators

If a technology generates chemical by-products, monitoring may show:

- Raised ozone levels in spaces where an ozone-generating device is operating.

- Elevated NOₓ or other gases when certain high-energy processes are used.

- Shifts in the VOC profile, including the appearance of more oxidised or fragmented compounds.

Laboratory tests can be configured to look specifically for these by-products by measuring incoming and outgoing air streams under controlled conditions.

Particle and microbial indicators

Secondary release from filters or surfaces may show up as:

- Unexpected spikes in particle counts, especially if they correlate with changes in fan speed, filter handling or disturbance.

- Changes in viable microbial counts in air samples without a clear new source.

In practice, these effects may be subtle and are often easiest to detect in controlled studies where conditions can be repeated with the device switched on and off.

What should building teams consider when evaluating secondary pollution risk?

The aim is not to avoid all active processes, but to select and operate systems in a way that minimises unintended side-effects.

A practical set of questions includes:

- Does this technology generate ozone or other oxidising gases in the room?

- Is there measured data for ozone and NOₓ under normal occupied-mode operation?

- What by-products have been measured in tests?

- Is there data showing whether any secondary pollutants were measured or reported during operation?

- What happens to captured particles and microbes?

- Does the system rely on filtration alone, or is there a mechanism for inactivating biological material (e.g. catalysis at the filter surface)?

- Is there evidence from realistic environments?

-

- Were tests carried out in a chamber for controlled performance and in the field to show behaviour in occupied buildings?

- Were both “desired” pollutants and potential by-products measured?

- Are noise, energy use and maintenance compatible with continuous long-term operation?

What are the practical implications for designing low–secondary-pollution strategies?

For most buildings, a sensible approach to secondary pollution is to layer controls and favour technologies that keep reactive chemistry where it belongs.

In practical terms:

- Use source control and ventilation as the foundation to limit the initial pollutant load.

- Apply mechanical filtration to remove particles, especially PM₂.₅ and bioaerosols.

- Where more advanced air cleaning is needed, prefer systems that:

- Confine oxidation to solid catalysts rather than relying on ozone or free radicals in the room air.

- Are backed by data showing pollutant removal without harmful by-products.

- Treat chemical fogging or aggressive oxidants as intermittent, controlled tools rather than permanent air treatment solutions for occupied spaces.

In summary, secondary air pollution shows that not all air “cleaning” is equal. Effective indoor air quality management focuses not just on how much pollution is removed, but also on what, if anything, is created in the process.

Latest News

What does “secondary air pollution” actually mean indoors?

Key points Secondary air pollution refers to new pollutants or re-released contaminants created as a side effect of…

What are the main indoor air pollutants in modern buildings?

Key points Indoor air pollutants in modern buildings are typically a mixture of particles, gases, vapours and bioaerosols…

What is indoor air quality and why does it matter for buildings?

Key points Indoor air quality (IAQ) describes the chemical, particulate, biological and physical characteristics of the air inside…